So what's the point of linear algebra, anyway?

Or: let's try to invent linear algebra, but backwards

Asking someone in a STEM field to justify linear algebra concepts is a bit like asking a Haskell programmer about monads. The best case scenario is that you’ll get a shrug and a “don’t worry about it, just learn when to use it”. The more common scenario is an hour-long explanation that leaves you more confused than when you started. In keeping with my lifelong passion for confusing and upsetting as many people as possible, today I would like to talk about linear algebra. (I’ll save the monads for a later date. Don’t worry, they’re just burritos.)

Target audience for this post: someone with at least a little exposure to linear algebra. If you’re starting from complete scratch and want a good high-level picture, I highly recommend 3Blue1Brown’s Essence of Linear Algebra series on YouTube. Though of course, even that is no substitute for an actual textbook.

Why all the vague definitions?

One of the reasons that linear algebra can be frustrating to the average high schooler or undergrad is that it’s often the first time in your life that you get exposed to the Mathematician Way of Doing Things™. That is, rather than working with relatively concrete definitions, like “a vector is a list of real numbers” (a.k.a. the physicist’s vector), you get far less helpful and less intuitive definitions, like “a vector is an element of a vector space”, and “a vector space is a set that satisfies all of these different properties that you definitely won’t remember and will definitely just end up visualizing as $\mathbb{R}^n$ anyway”.

There are basically two main benefits to doing things this way:

- Minimal assumptions. Structures like $\mathbb{R}^n$ have a LOT going on - they have a notion of distance, they have a notion of an inner product, you can even do calculus in them! Why make so many assumptions if you don’t need them to prove the theorem at hand?

- Broad applicability. This goes hand in hand with the above. By assuming as little as possible, you can find potentially unexpected applications for existing ideas with minimal extra effort.

In short: the math way of doing things is a programmer’s dream come true.1 Maximum code reuse! But a little more confusing than necessary for someone who just wants to think of vectors as arrows and spaces as grids.

Okay but seriously though what’s up with all of these arrays of numbers and tedious operations?

Now for the contentious part. I’m no pedagogy expert, but my ideal linear algebra course would change up the order of things a bit from the usual approach. In particular, the typical course goes something like this (e.g. in Gilbert Strang’s book):

- Vectors, matrices

- Lots and lots of number crunching: matrix-vector products, matrix multiplication, Gauss-Jordan elimination, determinants, etc.

- Even more number crunching, projections, various kinds of decompositions

- Nullspaces, bases, dimensions, kernels, etc.

- Eigenvalues and eigenvectors

- OH LOOK WE CAN FINALLY TALK ABOUT LINEAR TRANSFORMATIONS

Bluntly, while this ordering may make sense for someone whose idea of linear algebra starts and ends with BLAS and numpy.linalg, I think this approach tends to miss the forest for the trees. Don’t get me wrong: drilling the fundamentals is absolutely essential, and having concrete numbers to work with can make new math more approachable. But linear algebra is in the unfortunate situation of being a particularly useful subject that is also particularly obtuse from a purely numerical standpoint. And so in my ideal course, we would start from the other end and teach in the following order:

- Linearity and linear transformations

- Invent the concepts of a basis, vector, and matrix

- Invent matrix multiplication, eigenvalues and eigenvectors

- Invent the rest of linear algebra now that we have what we need to do so

I’m not sure if this would actually hold up in a real classroom, but regardless, I’d like to sketch out how this approach would work with the rest of this post.2 So let’s start with:

Linearity

Let’s finally try to answer the question in the title of the post. What is the point of linear algebra? My answer is simple:

Oh boy, if that isn’t circular. But I mean this sincerely. And to illustrate what I mean, let’s do something really mathematically inappropriate: I’ll show you a formula, and I won’t define any of the symbols in it. (Except $\forall$, which means “for all”.)

\[\forall a,b,\vec{x},\vec{y}: \quad T(a\vec{x} + b\vec{y}) = a T(\vec{x}) + b T(\vec{y})\]To me, that equation, and its many generalizations, are the absolute core of linear algebra. It doesn’t matter what $T$ and $\vec{x}$ and $a$ are. It doesn’t even matter what addition and multiplication mean (within reason). You can shuffle the definitions around however you like, as mathematicians are wont to do. What matters is the structure of the equation itself. Because when you view $T$ as a sort of function, and you view the above equation as a constraint on “linear” functions, you are basically saying the following:

In other words, to understand how $T$ acts on the complicated input $a\vec{x} + b\vec{y}$, we just need to know how it acts on $\vec{x}$ and $\vec{y}$. I argue that this one concept is so immensely powerful that it motivates all of the other concepts in linear algebra: from matrices to eigenvectors to everything else. The notion of a transformation that can be studied just by breaking down how it acts on specific inputs encompasses concepts as disparate as 3D rotations, the growth of the Fibonacci sequence, differentiation and integration, and the evolution of quantum states over time. For whatever reason, the universe is just full of transformations that can be broken down like this. And so correspondingly, we want our conception of these transformations to be broad enough to adequately capture this beautiful phenomenon in its myriad forms.3

Bases

To recap, we have now the vague half-concept of a “linear transformation” as some kind of operation that can be understood by examining how it acts on components of its input. But for a concept like this to be useful, we need to actually be able to break said input down into components in the first place. Hence the notion of a basis.

How delightfully backwards! How pleasantly vague! Let’s try to strip away some of this vagueness and pin down something more useful and algebraic. “Input to a linear transformation” is a mouthful, so let’s abbreviate that to the currently-meaningless term “vector”. Let’s assume our basis, our building blocks, consists of some set of mathematical objects $b_1, …, b_n$. Let’s assume that $\vec{x}$ is some complicated object (“vector”) and we want to understand how our lovely linear transformation $T$ behaves when you feed it $\vec{x}$.

To compute $T(\vec{x})$, then, we need to understand two things:

- How can we build our vector $\vec{x}$ out of our presumably useful building blocks $b_1, …, b_n$?

- How can we express how $T$ behaves on each of these building blocks?

Our one question has grown to two, but these seem more tractable. In particular, we can solve the former by inventing the coordinate vector, and the latter by inventing the dreaded matrix.

Coordinate vectors

We’ve got our building blocks $B = \{b_1, …, b_n\}$, and we’ve got our complicated object $\vec{x}$, so let’s take a first crack at building our $\vec{x}$ out of said building blocks.

Not a crazy idea. But we immediately run into a wall: if we have only a finite number of basis elements, then we can only express a finite number of vectors. In particular, if we’re only adding basis elements, then we can express at most $2^n$ vectors with this scheme. Even if we invent a symbol for subtraction, like $\vec{x} = b_1 - b_2$, that still only gives us $3^n$ possibilities - way too finite. How will we ever express all polynomials or all of the possible rotations of a 3D shape with just a finite number of vectors? No, this won’t do.

Let’s try a different approach. In addition to “adding” and “subtracting” basis elements (whatever that means), we’ll also allow for “scaling”. That is, we’ll throw some coefficients into the mix, and assume they behave reasonably like numbers.4 Since we use these things for “scaling”, we can call them “scalers”, sorry, scalars.

This gives us the axiom we want:

(Yes, I did sneak the extra “unique” in there; without it, we can have multiple ways to represent something with our basis, which is kind of annoying, as we’ll see in a moment.)

We can then define our basis $Q$ (for "quadratic basis") as the set of functions $\{q_0, q_1, q_2\}$ where $q_0: z \mapsto 1$, $q_1: z \mapsto z$, and $q_2: z \mapsto z^2$. Our function $f: z \mapsto az^2 + bz + c$ can then be rewritten using our new function-level addition and scaling operations as $f = aq_0 + bq_1 + cq_2$, which satisfies our axiom above. Proving that this representation is unique is left as an exercise, but should hopefully be self-evident.

Now that we have a nice notion of breaking a vector down into a basis, we notice something else. Since our basis is so great and reusable, there’s probably no need to keep writing it down. In fact, if we have lots of vectors, we can distinguish them from each other solely by breaking them down into this basis and examining the scaling factors. (This is why uniqueness matters - you don’t want two sets of scaling factors to give you the same vector!) So then we can simply hide away the $b_i$ and identify $\vec{x}$ with its coordinates $x_1,…,x_n$. The basis is still there, invisible, like the air you breathe. But there’s no need to talk about it unless you ever want to switch to a different basis.

Henceforth, then, we’ll refer to these scaling factors $x_i$ as the “coordinates” of $\vec{x}$ with respect to our basis $b_1, …, b_n$, and we’ll use the term “coordinate vector” to refer to the list of these coordinates $\begin{bmatrix}x_{1} & \dots & x_{n}\end{bmatrix}$. We can go from $\vec{x}$ to its coordinates by breaking it down along the basis elements, and we can go from the coordinate vector back to $\vec{x}$ just by using the handy sum $\vec{x} = \sum_{i=1}^n {x_i b_i}$. So far so good! We’ll use the following notation for coordinate vectors5:

\[\left[x\right]_B := \begin{bmatrix}x_{1} & \dots & x_{n}\end{bmatrix}\]Refining our notion of a vector

Earlier, we defined “vector” as “the input to a linear transformation”. But now that we have this clean concept of a basis, we can refine our informal definition a bit. Namely:

Note that this means that basis elements $b_i \in B$ are also vectors over $B$, because any basis element $b_i$ can be expressed as $b_i = 0 \times b_1 + … + 1 \times b_i + … + 0 \times b_n$. So we can now just call them basis vectors.

It’s worth noting that, modulo rigor, this definition of a vector is pretty much always equivalent to the traditional “a vector is an element of a vector space” definition, since every vector space has a basis.6 Speaking of which, let’s go ahead and define a vector space as well:

Note the careful phrasing; this basis isn’t necessarily unique for said vector space, but unlike the traditional definition, you do need to pick a basis to start with when you define a vector space.

Matrices

Recall that to understand $T(\vec{x})$, we needed to answer two questions:

- How can we build our vector $\vec{x}$ out of our presumably useful

building blocksbasis vectors $b_1, …, b_n$? - How can we express how our linear transformation $T$ behaves on each of these basis vectors?

The notion of a coordinate vector solves our first problem, but we still need to answer the second. And to do this, we’ll need to add a long-overdue restriction to our notion of a linear transformation:

In other words, we want to be able to understand both the input and output of $T$ by breaking them down into components, even if those components are completely different. Let’s just feed in one basis element to start, $b_1$. By our definition of a vector, we know that we can express $T(b_1)$ as a scaled sum of elements of some basis $C = \{c_1,…,c_m\}$ and get some coefficients, which we’ll call $t_{1,1}, …, t_{m, 1}$. We can use our handy concept of a coordinate vector to express the coordinates of $T(b_1)$:

\[\begin{align*} T(b_1) &= \sum_{i=1}^m {t_{i,1} c_i} \quad & \text{By the definition of a vector} \\[2ex] \left[T(b_1)\right]_C &= \begin{bmatrix}t_{1,1} & \dots & t_{m,1}\end{bmatrix} \quad & \text{Re-expressing as a coordinate vector} \end{align*}\]

But there are quite a few more input basis vectors than just $b_1$, so we may as well write out all of these components as a grid of numbers:

We’ll call this thing we just invented a matrix. There are two things to note here:

- Reifying $T$ into a concrete grid of numbers required us to use two bases, not just one. Hence the notation $[T]_{B,C}$.

- We’ve written down all of our components, but that doesn’t actually help us do anything yet. We’re still not sure what $T(\vec{x})$ is.

- $D(q_0) = D(z \mapsto 1) = z \mapsto 0$.

- $D(q_1) = D(z \mapsto z) = z \mapsto 1$.

- $D(q_2) = D(z \mapsto z^2) = z \mapsto 2z$.

$$ \left[D\right]_{Q,Q} = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 2 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} $$

The second point above segues nicely into our next topic:

Matrix-vector multiplication as an efficient shorthand for function application

At this point we have all of the puzzle pieces. We have clean, concrete representations of $\vec{x}$ and $T$ relative to our well-understood basis vectors. Now all we need to do is find a good representation of $T(\vec{x})$. This representation will invariably be in the form of coordinates with respect to the basis $C$. With this, we’ll finally have a full, concrete understanding of $T(\vec{x})$. In essence, we’re replicating the green arrow below with the three white arrows:

As the diagram suggests, the missing piece here is the notion of matrix-vector multiplication. We simply take the dot product of each row of $\left[T\right]_{B,C}$ with $[x]_B$ to get the coordinates of $T(\vec{x})$ in the basis $C$. The proof for this is quite elegant:

We can now read off the $j$-th element of our result above, $\sum_{i=1}^n {t_{j,i} x_i}$, and call it the “dot product” of the coordinate vectors $\begin{bmatrix}x_{1} & \dots & x_{n}\end{bmatrix}$ (our input) and $\begin{bmatrix}t_{j,1} & \dots & t_{j,n}\end{bmatrix}$ (the $j$-th row of our original matrix $\left[T\right]_{B,C}$). Feel free to quickly check that this is, indeed, the same thing as the traditional definition of a dot product.

And now that we have this compact way to compute $\left[T\left(\vec{x}\right)\right]_C$ as a coordinate vector of dot products, we can abbreviate this computation as our definition of a matrix-vector product.

\[\left[T\right]_{B,C}\left[x\right]_B := \begin{bmatrix}\sum_{i=1}^n {t_{1,i} x_i} & \dots & \sum_{i=1}^n {t_{m,i} x_i}\end{bmatrix}\]And that’s it! It’s worth meditating on that proof for a little bit. Matrix-vector multiplication isn’t just some meaningless symbol shuffling: we’ve derived exactly the computations necessary to go from a representation of $\vec{x}$ to a representation of $T(\vec{x})$. Of course, now that we’ve worked through a justification for this notation instead of just having a definition presented to us, we know that “product” is a bit of a misnomer, and this is really just an efficient method of function application.

A similar process can be used to invent matrix-matrix multiplication: it’s just function composition, carried out numerically. This one is left as an exercise for the reader :D

Some conclusions

Originally, I had planned to go further with this post, inventing eigenvectors as “particularly nice basis vectors” which allow you to just think of your transformation as scalings, and then introducing the Fourier transform as an eigendecomposition for the second derivative operator. But I think I’ve made the high-level idea clear enough now, so let’s skip to conclusions.

In short, I don’t think it’s necessarily optimal to teach linear algebra the way it is taught traditionally, with a deluge of mechanical rigmarole preceding any conceptual justification for why we do things the way we do. Worse, I think that obfuscating the centrality of linear transformations actually undersells the broad applicability of linear algebra, since priming students to think of the subject as just manipulating grids of numbers makes them less equipped to grasp other kinds of vector spaces, especially function spaces.

Heck, linear algebra is so broadly useful that we will go out of our way to make things linear when we can - whether we’re linearizing differential equations or using representation theory to convert all kinds of algebraic structures into linear transformations.

Does that mean you should ditch Gilbert Strang and actually teach things the way this blog post does? Well, probably not. For starters, the more traditional, axiomatized definition of a vector space is better suited to preparing a student for future mathematics courses. But I think there is a pedagogical middle ground here that doesn’t leave linear transformations as an afterthought, and I hope that I’ve at least shown that the idea to front-load linear transformations isn’t without merit. In particular, I think that emphasizing the centrality of linear transformations also primes students to better understand other structure-preserving maps in the future, such as group/ring/etc homomorphisms, continuous functions between topological spaces, and so on.

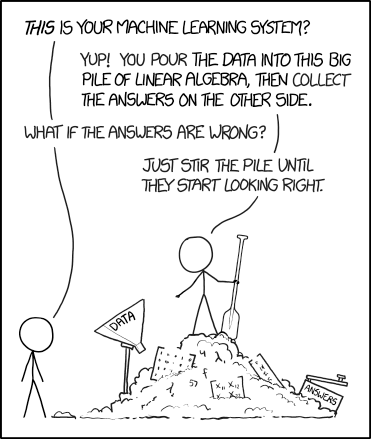

One thing I have not mentioned yet is that part of linear algebra’s usefulness comes not just from its mathematical universality, but from how amenable it is to being automated on modern hardware. The natural parallelizability of matrix multiplication has allowed us to build larger and faster GPUs to crunch numbers in quantities that have a quality all of their own. The entire modern field of deep learning hinges on this, as do other kinds of numerical methods and physical simulation.

Even quantum computers are really just chains of matrix multiplications when it comes down to it.

In a way, trying to explain how useful linear algebra is before actually teaching it may be a fool’s errand; like a prisoner staring at dancing shadows on the wall of Plato’s cave, sometimes you just have to understand something for yourself before it can really click. But that doesn’t mean that we can’t help people turn around so they can see the vast world that lay unnoticed behind them.

Footnotes

-

An aside for programmers: the math way of defining structures can be thought of as defining interfaces or protocols, like

VectorSpaceorTopologicalSpaceorRing, and then letting any arbitrary concrete structure implement said interface if it satisfies the necessary properties (i.e. a structural type system). In a sense, the structuralist point of view on math is that it’s only these interfaces that really matter, not the underlying concrete objects that implement them. So the natural numbers, for example, could just as well be any sequence of things with the right properties to be assigned the labels of “one” and “two” and so on, not just one particular canonical set of mathematical objects. This is a bit like programming while only paying attention to your type system and contracts and never once thinking about the actual bytes that you’re shuffling around. Which, well, is exactly what math is, from the Curry-Howard perspective. But now we’re getting REALLY off topic. ↩ -

In particular, what I’m aiming for here is a little reverse mathematics, where rather than presenting definitions as a fait accompli and deriving theorems, I want to work backwards from our desired properties to figure out what definitions would get us there. ↩

-

For the sake of clarity, though, I will cheat a little bit and stick to finite-dimensional reasoning for most of this post. Pretty much everything should be generalizable to the infinite-dimensional case. ↩

-

More specifically, we assume they come from a field, i.e. have reasonable definitions of addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division with reasonable concepts of 0 and 1. If you give up on division you still have a ring, which means that we end up defining modules instead of vector spaces, which are still pretty nice but way beyond the scope of this post. ↩

-

At the expense of being confusingly nonstandard, I’m going to write out coordinate vectors as rows instead of columns, because that makes them easier to write inline and I don’t want to justify the concept of transposing just to write ^T everywhere for no real benefit. ↩

-

The caveat here is that the proof that every vector space has a basis requires the axiom of choice, but that axiom’s basically a given if you want to have any fun anyway. ↩